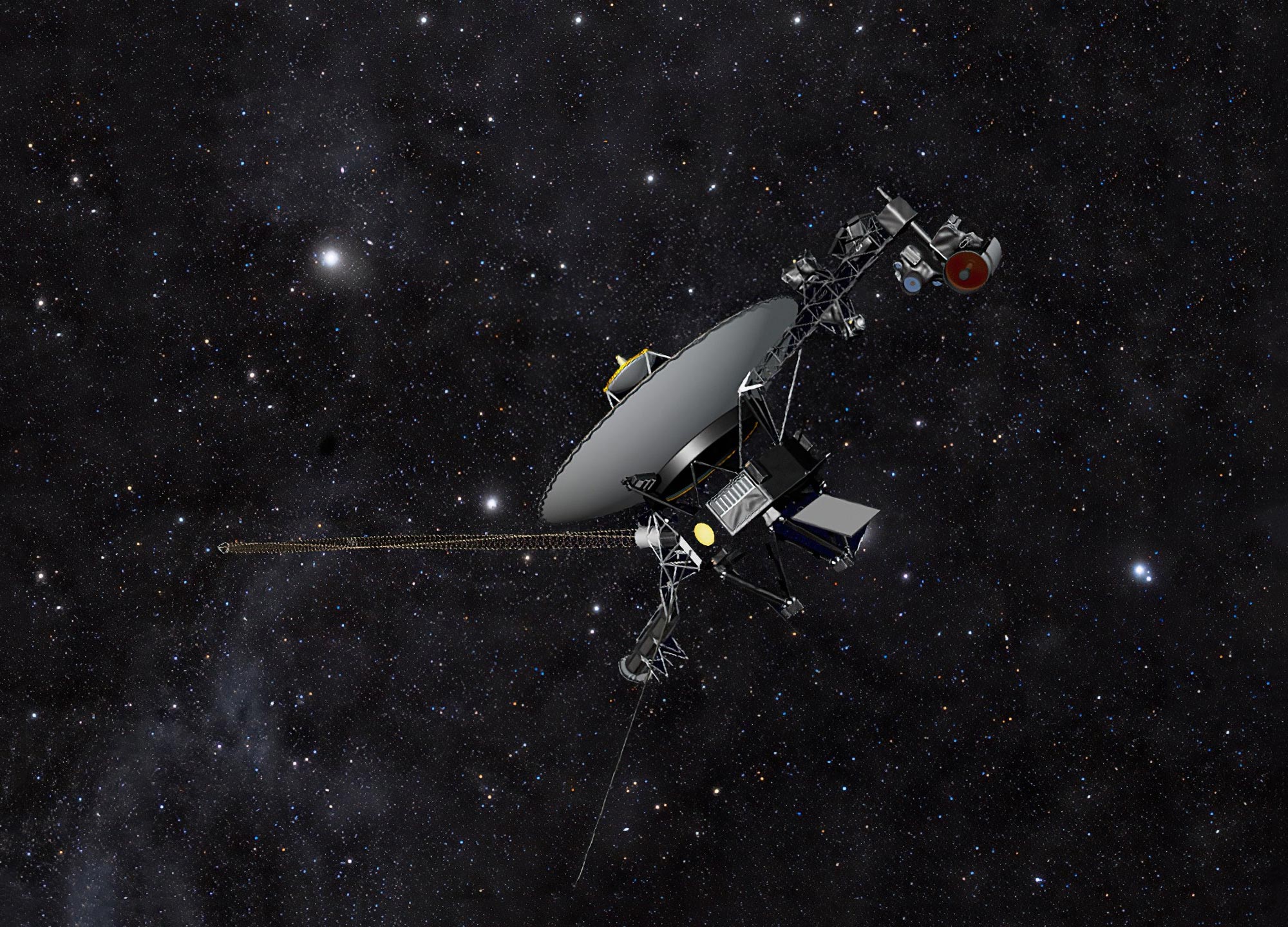

Ez a művész koncepciója a NASA Voyager űrszondáját mutatja be egy csillagmezővel szemben az űr sötétjében. A két Voyager űrszonda egyre messzebbre utazik a Földtől, a csillagközi térbe utazik, és végül a Tejútrendszer középpontja körül kering majd. Köszönetnyilvánítás: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A terv szerint a Voyager 2 tudományos műszerei a korábban vártnál néhány évig tovább működnek, így több felfedezést tesznek lehetővé a csillagközi térből.

Az 1977-ben felbocsátott Voyager 2 űrszonda több mint 12 milliárd mérföldre (20 milliárd kilométerre) van a Földtől, és öt tudományos műszerrel vizsgálja a csillagközi teret. Annak érdekében, hogy ezek a műszerek a csökkenő áramellátás ellenére is működőképesek legyenek, az elöregedő űrszonda egy fedélzeti biztonsági mechanizmus részeként félretett kis tartalék áramforrást kezdett használni. A lépés lehetővé tenné a misszió számára, hogy az idei év helyett 2026-ig halasszák el egy tudományos műszer bezárását.

Egy tudományos műszer kikapcsolása nem fejezi be a munkát. Miután 2026-ban leállítottak egy műszert, a szonda továbbra is négy tudományos műszert fog táplálni mindaddig, amíg az alacsony teljesítményű tápegység egy másik leállítását nem igényli. Ha a Voyager 2 egészséges marad, a mérnöki csapat arra számít, hogy a küldetés még évekig folytatódik.

Az 1976-ban a JPL űrszimulációs termében bemutatott Voyager proof tesztmodell az 1977-ben felbocsátott iker Voyager űrszondák pontos mása volt. A modell földmérő platformja jobbra nyúlik, és az űrszonda számos tudományos műszerét tartalmazza. . pozíciókat. Köszönetnyilvánítás: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A Voyager 2 és ikerpárja, a Voyager 1 az egyetlen két űrszonda, amely a helioszférán, a Nap által generált részecskékből és mágneses mezőkből álló védőbuborékon kívül működik. A szondák segítenek a tudósoknak megválaszolni a helioszféra formájával és a Földnek a csillagközi környezet energetikai részecskéitől és egyéb sugárzásaitól való védelmében betöltött szerepével kapcsolatos kérdéseket.

– mondta Linda Spilker, a Voyager projekt tudósa[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which manages the mission for NASA.

Power to the Probes

Both Voyager probes power themselves with radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which convert heat from decaying plutonium into electricity. The continual decay process means the generator produces slightly less power each year. So far, the declining power supply hasn’t impacted the mission’s science output, but to compensate for the loss, engineers have turned off heaters and other systems that are not essential to keeping the spacecraft flying.

With those options now exhausted on Voyager 2, one of the spacecraft’s five science instruments was next on their list. (Voyager 1 is operating one less science instrument than its twin because an instrument failed early in the mission. As a result, the decision about whether to turn off an instrument on Voyager 1 won’t come until sometime next year.)

Each of NASA’s Voyager probes are equipped with three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), including the one shown here. The RTGs provide power for the spacecraft by converting the heat generated by the decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In search of a way to avoid shutting down a Voyager 2 science instrument, the team took a closer look at a safety mechanism designed to protect the instruments in case the spacecraft’s voltage – the flow of electricity – changes significantly. Because a fluctuation in voltage could damage the instruments, Voyager is equipped with a voltage regulator that triggers a backup circuit in such an event. The circuit can access a small amount of power from the RTG that’s set aside for this purpose. Instead of reserving that power, the mission will now be using it to keep the science instruments operating.

Although the spacecraft’s voltage will not be tightly regulated as a result, even after more than 45 years in flight, the electrical systems on both probes remain relatively stable, minimizing the need for a safety net. The engineering team is also able to monitor the voltage and respond if it fluctuates too much. If the new approach works well for Voyager 2, the team may implement it on Voyager 1 as well.

“Variable voltages pose a risk to the instruments, but we’ve determined that it’s a small risk, and the alternative offers a big reward of being able to keep the science instruments turned on longer,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager’s project manager at JPL. “We’ve been monitoring the spacecraft for a few weeks, and it seems like this new approach is working.”

The Voyager mission was originally scheduled to last only four years, sending both probes past Saturn and Jupiter. NASA extended the mission so that Voyager 2 could visit Neptune and Uranus; it is still the only spacecraft ever to have encountered the ice giants. In 1990, NASA extended the mission again, this time with the goal of sending the probes outside the heliosphere. Voyager 1 reached the boundary in 2012, while Voyager 2 (traveling slower and in a different direction than its twin) reached it in 2018.

More About the Mission

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of Caltech in Pasadena, built and operates the Voyager spacecraft. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

„Utazási specialista. Tipikus közösségi média tudós. Az állatok barátja mindenhol. Szabadúszó zombinindzsa. Twitter-barát.”

More Stories

A SpaceX Polaris Dawn űrszondájának legénysége a valaha volt legveszélyesebb űrsétára készül

Egy őskori tengeri tehenet evett meg egy krokodil és egy cápa a kövületek szerint

Egyforma dinoszaurusz-lábnyomokat fedeztek fel két kontinensen