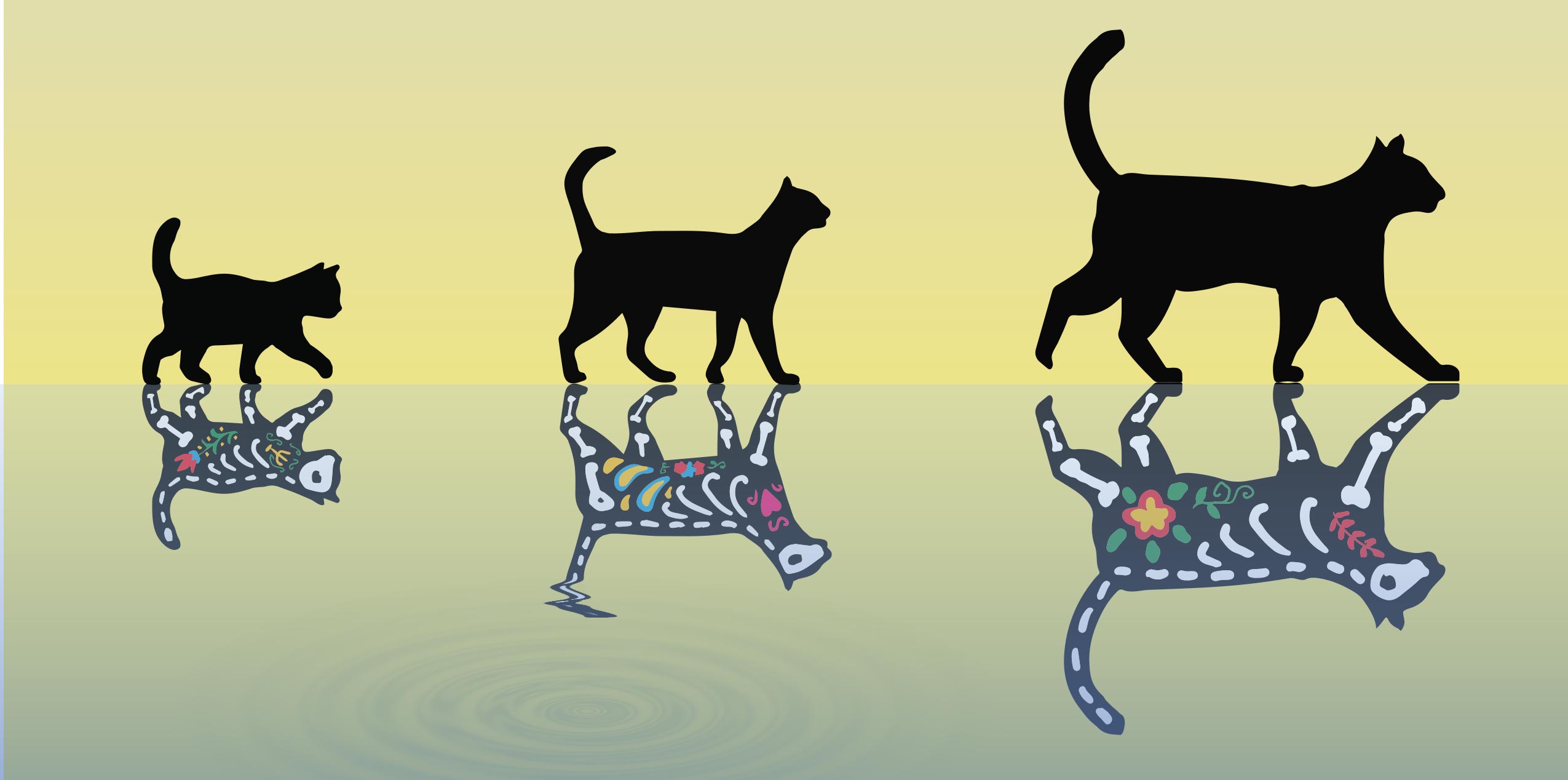

Az ETH Zürich tudósai előrehaladást értek el Schrödinger nehezebb macskáinak létrehozásában, amelyek egyszerre lehetnek élők (fent) és halottak (alul). Köszönet: Yiwen Chu / ETH Zürich

Az ETH Zürich kutatói az eddigi legnehezebb Schrödinger macskát hozták létre úgy, hogy egy kristályt két rezgésállapot szuperpozíciójába helyeztek. Eredményeik erősebb qubitekhez vezethetnek, és segíthetnek megmagyarázni, miért nem figyelik meg a qubiteket a mindennapi életben.

- Az ETH Zürich kutatói megalkották Schrödinger eddigi legnehezebb macskáját.

- Ehhez kombináltak egy oszcilláló kristályt egy szupravezető áramkörrel.

- Azt remélik, hogy jobban megértik, miért tűnnek el a kvantumhatások a makroszkopikus világban.

Még ha nem is kvantumfizikus, valószínűleg hallott már Schrödinger híres macskájáról. Erwin Schrödinger egy 1935-ös gondolatkísérletben olyan macskákat talált ki, amelyek egyszerre lehetnek élők és halottak is. A nyilvánvaló paradoxon – elvégre a mindennapi életben csak olyan macskákat látunk, amelyek vagy élnek, vagy élnek. vagy Halott – arra késztette a tudósokat, hogy megpróbáljanak hasonló helyzeteket megvalósítani a laborban. Eddig úgy tudták ezt megtenni, hogy például atomokat vagy molekulákat használtak kvantummechanikai szuperpozíciós állapotban, hogy egyszerre két helyen vannak.

Az ETH-n Yiwen Chu, a Szilárdtestfizikai Laboratórium professzora által vezetett kutatócsoport drámaian nehezebb Schrödinger macskát hozott létre úgy, hogy egy kis kristályt két rezgésállapot szuperpozíciójába helyezett. A Science tudományos folyóiratban a héten közzétett eredményeik erősebb qubitekhez vezethetnek, és rávilágíthatnak arra a rejtélyre, hogy miért nem figyelnek meg kvantum-szuperpozíciókat a makroszkopikus világban.

macska egy dobozban

Schrödinger eredeti gondolatkísérletében egy macskát egy fémdobozba zárnak radioaktív anyagokkal, egy Geiger-számlálóval és egy fiola méreggel. Egy bizonyos időkeretben – például egy óra -[{” attribute=””>atom in the substance may or may not decay through a quantum mechanical process with a certain probability, and the decay products might cause the Geiger counter to go off and trigger a mechanism that smashes the flask containing the poison, which would eventually kill the cat. Since an outside observer cannot know whether an atom has actually decayed, he or she also doesn’t know whether the cat is alive or dead – according to quantum mechanics, which governs the decay of the atom, it should be in an alive/dead superposition state. (Schrödinger’s idea is commemorated by a life-size cat figure outside his former home at Huttenstrasse 9 in Zurich).

In the ETH Zurich experiment, the cat is represented by oscillations in a crystal (top and blow-up on the left), whereas the decaying atom is emulated by a superconducting circuit (bottom) coupled to the crystal. Credit: Yiwen Chu / ETH Zurich

“Of course, in the lab we can’t realize such an experiment with an actual cat weighing several kilograms,” says Chu. Instead, she and her co-workers managed to create a so-called cat state using an oscillating crystal, which represents the cat, with a superconducting circuit representing the original atom. That circuit is essentially a quantum bit or qubit that can take on the logical states “0” or “1” or a superposition of both states, “0+1”. The link between the qubit and the crystal “cat” is not a Geiger counter and poison, but rather a layer of piezoelectric material that creates an electric field when the crystal changes shape while oscillating. That electric field can be coupled to the electric field of the qubit, and hence the superposition state of the qubit can be transferred to the crystal.

Simultaneous oscillations in opposite directions

As a result, the crystal can now oscillate in two directions at the same time – up/down and down/up, for instance. Those two directions represent the “alive” or “dead” states of the cat. “By putting the two oscillation states of the crystal in a superposition, we have effectively created a Schrödinger cat weighing 16 micrograms,” explains Chu. That is roughly the mass of a fine grain of sand and nowhere near that of a cat, but still several billion times heavier than an atom or molecule, making it the fattest quantum cat to date.

In order for the oscillation states to be true cat states, it is important that they be macroscopically distinguishable. This means that the separation of the “up” and “down” states should be larger than any thermal or quantum fluctuations of the positions of the atoms inside the crystal. Chu and her colleagues checked this by measuring the spatial separation of the two states using the superconducting qubit. Even though the measured separation was only a billionth of a billionth of a meter – smaller than an atom, in fact – it was large enough to clearly distinguish the states.

Measuring small disturbances with cat states

In the future, Chu would like to push the mass limits of her crystal cats even further. “This is interesting because it will allow us to better understand the reason behind the disappearance of quantum effects in the macroscopic world of real cats,” she says. Beyond this rather academic interest, there are also potential applications in quantum technologies. For instance, quantum information stored in qubits could be made more robust by using cat states made up of a huge number of atoms in a crystal rather than relying on single atoms or ions, as is currently done. Also, the extreme sensitivity of massive objects in superposition states to external noise could be exploited for precise measurements of tiny disturbances such as gravitational waves or for detecting dark matter.

Reference: “Schrödinger cat states of a 16-microgram mechanical oscillator” by Marius Bild, Matteo Fadel, Yu Yang, Uwe von Lüpke, Phillip Martin, Alessandro Bruno and Yiwen Chu, 20 April 2023, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adf7553

„Utazási specialista. Tipikus közösségi média tudós. Az állatok barátja mindenhol. Szabadúszó zombinindzsa. Twitter-barát.”

More Stories

A SpaceX Polaris Dawn űrszondájának legénysége a valaha volt legveszélyesebb űrsétára készül

Egy őskori tengeri tehenet evett meg egy krokodil és egy cápa a kövületek szerint

Egyforma dinoszaurusz-lábnyomokat fedeztek fel két kontinensen